Cheat Sheet for an Agile Nation

Why do some places prosper while others decline?

Why do some towns improve their services while others cut services to the bone? How can one village struggle with potholes while the neighboring village stays in good repair? Why do American cities struggle to meet housing demand, no matter how hard they try?

The reason is productivity.

Efficiency isn’t enough for places to prosper. Efficiency simply describes the amount we accomplish relative to the resources that we spend. We can efficiently do the wrong thing.

To truly prosper, we need to generate value. How much value do we generate for the amount of resources we spend? That measure is productivity. The more value we create for a given set of resources, the more productive we are, and the more we prosper.

Destroying or diminishing value is counterproductive. We cannot be considered productive when doing the wrong things.

But productivity isn't as simple as we think.

To assess and improve productivity, we need to measure two factors: the value we’re creating and the resources we spend. But that’s easier said than done.

Value is subjective.

What we value depends on who we are. Principles differ from person to person and place to place. It takes work to uncover the principles that we share and ways to productively live up to them.

Value can be hard to measure.

Some things are relatively easy to measure: speed, production, timeliness. We measure tangible things without skipping a beat. But what about intangible things? Security, opportunity, community... It’s hard to measure what you can’t put in a box. Without measurement, tracking progress becomes difficult.

Value is distributed unevenly.

Few programs benefit all stakeholders equally. When measuring productivity, we need to ask who the beneficiaries will be. Will our value creation serve one group more than another? Will that “lumpiness” produce a balanced society, or will it amplify imbalances that are already in play?

Our usual methods for achieving productivity might not work today.

There are two fundamental systems for increasing productivity: scale-driven thinking and agile thinking. Each of them can be productive, but under different circumstances. So we have to know our circumstances to choose the system that will work for us.

In pre-industrial times, that was easy. Nearly everything was agile. You could turn on a dime, because you only made a few things at once. Travel was difficult, which made shipping and export uneconomical for most goods. Markets were therefore more local than they are today. This made them relatively small, so you couldn't sell in volume if you wanted to.

As history progressed and the movement of goods became easier, the scope of markets expanded. Technological advances enabled early adopters to produce a surplus of goods at lower cost. They could sell more goods because they could price the goods favorably, and markets were growing big enough to absorb the surplus.

In those circumstances, the more goods a producer made, the more profit they made. Mass production became the way to create wealth.

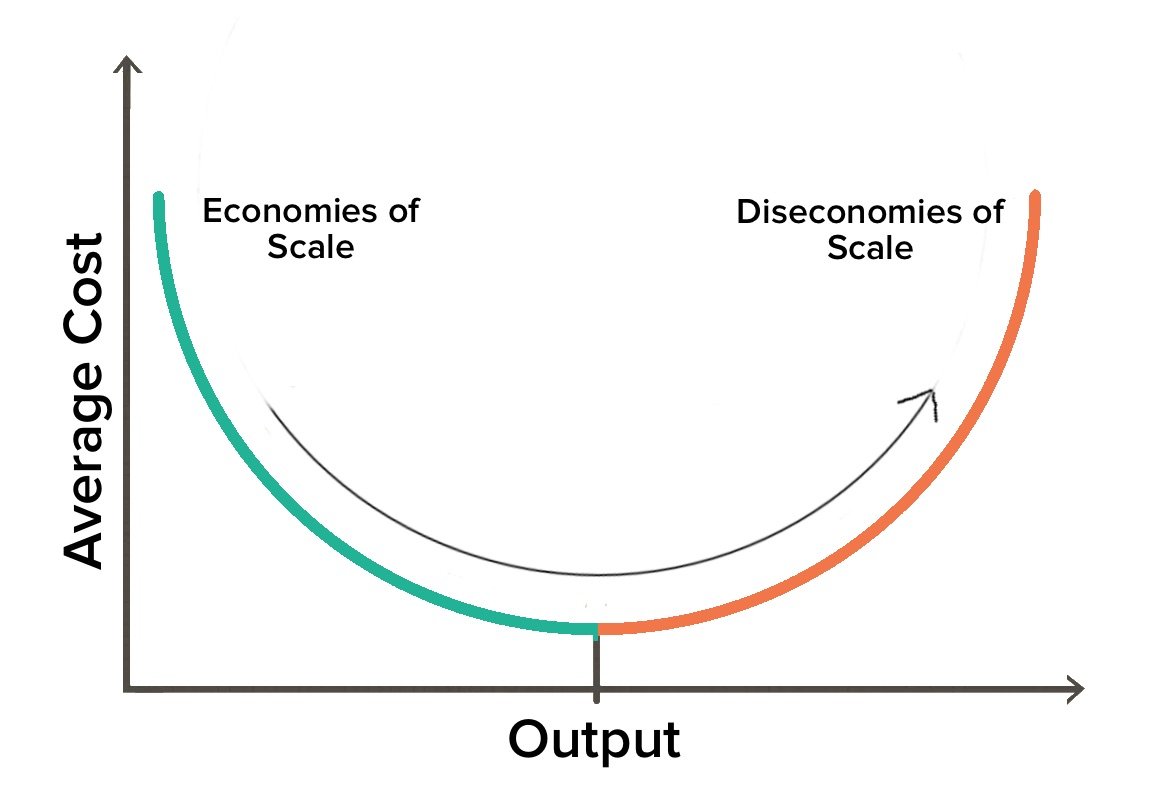

We've been in this phase of history for so long now that something funny has happened. We've taken mass production and scale-driven thinking so far that we've begun to achieve diseconomies of scale. The principles that made us productive before have become counterproductive in many areas. But those principles are so embedded in our way of thinking that we fail to realize when they lead us astray.

Under these circumstances, agile thinking provides an antidote.

Agile thinking is a way of organizing production to make it more responsive. We do this by improving how things flow in our work, whether those things are processes, material, or information.

Sometimes, we improve the flow by identifying waste that creeps into our work and keeps us from performing our best. When we eliminate waste, our work proceeds smoothly, and we consume fewer resources to get the job done.

Other times, It’s a matter of speeding up the feedback loop by which we learn and improve. The faster we learn, the sooner we achieve the outcomes we seek, and the fewer resources we consume to get there.

Or we might reduce the division of labor and specialization that are central to mass production and instead cross-train workers so they can flex as needed to keep production flowing.

Agile techniques like these enable us to improve our productivity in ways that are challenging to scale-driven enterprises by their very nature. To work in agile fashion, we have to be willing to approach our work incrementally and potentially course-correct midstream. But mass production depends on standardization across large batches; incrementalism and mid-stream changes would put big-batch standardization at risk.

Toyota, the automaker, famously used this conflict to its advantage when it developed new ways of operating after World War II. With a much smaller domestic market, Toyota couldn’t hope to reach the economies of scale that American automakers could.

Instead, they developed economies of agility. Practices such as cross-training, “pull” systems, and line-stop buttons enabled Toyota, and eventually other automakers, to produce high-quality cars efficiently, despite low production volumes. By 1970, Toyota’s agile practices made the company so productive that it could produce twice as many cars per worker than its American counterparts, with a comparable level of capital investment and fixed assets.

Agile thinking can work for a broad spectrum of activities.

The agile practices that made Toyota more productive aren’t confined to Japanese culture or to the automotive industry. They’ve been successfully adapted to software production and entrepreneurship, as well. Agile practices have even been used in municipal government to test streetscape improvements — a form of prototyping known as tactical urbanism.

Not every situation calls for agile thinking, but it can make a big difference for situations that do. If we want to help our cities become more productive and prosper, we need to add agile practices to our toolkit.

This “cheat sheet” is a start.

Think of it as a statement of guiding principles, or a checklist to help you diagnose what's going wrong in the place you call home. If you need a hand applying it, I’ll be happy to help.

"Cheat Sheet for an Agile Nation" debuted on May 1, 2015 at the 23rd Annual Congress for the New Urbanism.

Contact

Want to get in touch? Please feel free to drop me a line via LinkedIn.